Sean Paul: ‘A new generation are making dancehall their own’

Sean Paul is a party-starter. Few artists have a back catalogue better primed for the dancefloor than the multimillion-selling Jamaican artist. This year marks 20 years since his breakout second album, Dutty Rock, took the syncopated, bass-driven genre of dancehall global with hits Get Busy, Like Glue and Gimme the Light. In the ensuing years, Paul has had three US No 1s, a Grammy and collaborations with the biggest names in pop, including Beyoncé, Sia, Dua Lipa and Little Mix.

Now he is readying for the release of his eighth album, Scorcha. It plays like peak Paul: undulating bass and tripping rhythms backing up energetic lyrics on the subject of girls and ganja. It’s well-trodden territory, drawing on his decades of experience whipping the dancefloor into a frenzy. Yet Paul is now 49 and a father of two – five-year-old Levi Blaze and two-year-old Remi – and his life has expanded beyond the bravado; outside his music, there is more to him than just the party. Perhaps there always was.

On a muggy afternoon, we meet in an airless room at the Observer office. Paul is surrounded by his black-clad entourage and decked out in the signifiers of opulent success: gold chains, box-fresh Burberry kicks, a diamond pinky ring so large it’s a miracle his wrist remains intact, gold fangs covering his incisors and a pair of shades. Look and listen longer, though, and his brash surface starts to fragment: there are flecks of grey in his beard, he smells of jasmine, not smoke, and when he speaks, his instantly recognisable baritone is thoughtful, measured and soft.

Born Sean Paul Ryan Francis Henriques in Kingston, Jamaica in 1973, he struggled to find his place growing up. “From 13 to 19 years old, me and my brother spent our lives just trying to fit in,” he tells me, his dark glasses revealing a glimpse of his watery eyes. “We didn’t belong. I wanted to write about the social differences in Kingston, as that’s what I had experienced, but the party boy, the girl songs – that was just what people wanted.”

Prior to his teenage years, Paul lived a relatively uneventful life in the middle-class Uptown district of Kingston. His parents were both champion swimmers – his father held the national butterfly record and his mother was breaststroke champion – and they instilled in him a love of water sports, which culminated in Paul representing Jamaica at water polo from the age of 13 to 21. His aunt ran a sound system with her husband, who was a member of the ska band the Vagabonds, and at weekends the family would set up shop on their grandmother’s lawn, charging entry for punters to dance to the latest dub and reggae mixes.

“It was a party place and that was the first time I realised: I love this shit,” Paul says with a rumbling laugh. “It was exciting to watch people do what my grandma would call ‘the naughtiness’: the close dancing and smoking and drinking. Those were the proper house parties I wrote about later in songs like Get Busy.”

Amid the partying, though, things were beginning to destabilise at home. Paul’s father was one of seven children born to one of the leading historic Jamaican families, the Henriques, and he was the black sheep. “My dad got this reputation of being an Uptown bad boy,” Paul says. “He would hang out in the ghettos and smoke marijuana a lot. He didn’t want a job beneath his cousins in the family, he wanted to make it for himself. So he was always trying to hustle and he kept getting in trouble.”

When Paul was 13, his father was arrested on charges of manslaughter and was sentenced to 15 years in prison. “I lost my dad and I couldn’t understand when I would ever see him again, since a 15-year sentence was longer than my entire life at that point,” Paul says. His mother struggled to keep him and his brother at their private school and they ended up at Wolmer’s public school in Downtown, thrust into a new facet of Kingston life. “We would venture into the ghetto and smoke the chalice pipe and people would look at us and say, ‘You guys are privileged’, even though we couldn’t always afford gas for the car and the roof in our house was leaking,” Paul says. “Still, these people were really suffering. They lived in a zinc shack and it made me realise that I did not have it bad at all.”

With his father in jail and Paul adjusting to the nuances of a newfound status – too privileged for the ghetto and too poor for private school – he looked to other father figures for inspiration. “I followed successful sportspeople, like Michael Jordan and Mike Tyson,” Paul says. “But my main inspiration was Bob Marley. His son Damian was in the same year as my brother, so I was very aware of their family’s presence, but when I was 17 I really began paying attention to what he was saying in his songs.” In Marley’s socially conscious lyrics, Paul saw the means of expressing his own reality, but where Marley was writing to the aortic pulse of reggae, Paul began to write his verses to the frenetic thump of modern dancehall, which had come out of Kingston clubs and the sound system culture.

By the time Paul was 19, his father was released from jail for good behaviour and he had a handful of demos to share with him. “I was determined to talk about the disparity of Uptown and Downtown,” he says. “But producers would look at me and say, ‘You’re a face boy, an Uptown kid, why are you singing about poor people’s problems that nobody’s gonna believe?’”

In the face of mounting rejections, college assignments for his course in hotel management and water polo competitions, Paul says his resolve to tackle social injustices through music started to waver. “I got to the point where I was just hustling – I was charging to do vocal features on any tracks and in 1996, I decided to write a song about girls,” he says. That song became Baby Girl, a sparse, singsong track on which Paul entreats his love interest to let him comfort her. It was a smash hit on Jamaican radio and in the clubs. The price for those vocal features soon went up and he decided to quit water polo to focus on music.

“It was a sensation and ever since 1996, it’s been a different life,” he says. “Suddenly, I was a one-hit wonder and I knew I had to follow it up. People told me it wouldn’t last and that lit a fire in me to prove them wrong.” Paul tasked himself with writing and recording one song a day, beginning a six-year period of minimal sleep, fuelled by his hunger to produce new hits.

He has since embraced collaboration, working with pop acts such as the Saturdays while keeping his patois flow intact, ultimately helping to cement dancehall as a global genre. Its rhythms can now be felt underpinning everything from Drake’s Controlla to Justin Bieber’s Sorry and Ed Sheeran’s Shape of You. As the genre takes off and assimilates into pop, though, Paul is concerned that a lack of recognition of its roots means dancehall is at risk of being diluted beyond recognition.

“I’ve been extremely successful but I still don’t think people respect my footprint and the dancehall footprint in the business,” Paul says. “People say, ‘Dancehall is not getting on the radio any more’, but Ed Sheeran, Shawn Mendes, French Montana, they’re all doing it – they just don’t give the genre the credit to say, ‘This is my dancehall single.’” Indeed, when Bieber was questioned in 2021 about the use of his syncopated rhythms on the single Sorry, he simply labelled it “island music”.

While certain artists might shy away from genre designations out of fear of being pigeonholed, Paul sees the dancehall tag as a key facet of his and his peers’ identities and a flag to fly in the face of others who perhaps overlook their contributions. “Before the pandemic, I got tired of recording the pop features,” he says. “When we do a foreign collaboration, it’s always us working the record extra hard and they’re never too involved. They don’t care. We need to celebrate ourselves as the dancehall community instead – people like Beenie Man and Shaggy and Shabba Ranks, they all need their accolades – otherwise people just say Drake is innovative. No. It’s our rhythms and it’s our lingo in their music.”

Much of that lingo has now become commonplace singalong fare, even if the majority of Paul’s international audiences might have no idea what it means. In the early 2000s, during one of his many songwriting sessions, Paul wrote some of his most famous lines, based on his experiences clubbing in New York the previous week. “I sang, ‘Just gimme the light and pass the dro/Buss another bokkle a Moë’ [“pass the homegrown/ Open another bottle of Moët”]. Next thing, it’s on MTV and every radio station,” he says. But he wasn’t immediately pleased. “I was embarrassed at first. I used to have songs with bridges, but this is just a quick hook and two verses that kept repeating. It felt so simple.”

That song, Gimme the Light, was Paul’s first international hit, charting in the Top 10 in the US and UK. It taught Paul a lasting lesson about his role in the music industry. “I was having fun in the booth when I wrote it and I realised people could feel that vibe when they heard it, they wanted to have the same party experience,” he says. “I accepted that if this is me, then this is me. This is what I have to offer to the music game.”

He harnessed that freestyle, easygoing recording method and stardom followed. R&B singer Blu Cantrell featured Paul on her 2003 UK No 1, Breathe, and a newly solo Beyoncé enlisted Paul to feature on her single Baby Boy. When he was listening to the instrumental for the Beyoncé session in his car, a mango dropped through the sunroof and into his lap. “You don’t get a better sign than that,” Paul says with a laugh.

The fruit may have been a flash of Newtonian inspiration but there were also other, more serious interventions needed. “From 96 to 2002, I was just having fun but it soon got me into some pretty stupid times,” he says with a pause. “It was too much drinking, like getting up and going to the bottle of Hennessy in the hotel room. There were a lot of girls too, which is awesome, but after a while I realised, this is just too much everything. It could be killing me.”

Paul tempered the excess and settled down with Jodi Stewart, whom he married in 2012, but he kept producing the pleasure-seeking tunes the public craved from him. “I’m not doing a song a day now, but I still do a lot of music,” he says. “Scorcha has 16 tracks and I just did an album with 16 tracks [Live N Livin] in March 2021. I’m recording new music for the next record too. It doesn’t really stop and when I get into the studio mode, I’ll do five songs in a row.”

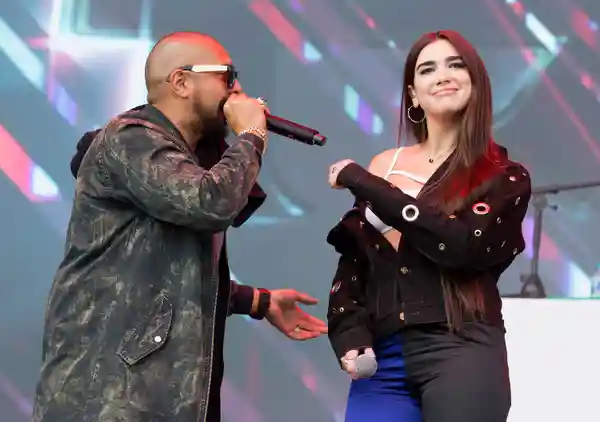

Paul’s immense work ethic doesn’t always pay off: Full Frequency, from 2014, for instance, sold fewer than 5,000 copies in the US, leading Paul to part ways with his label and to briefly become an independent artist again. But he took the opportunity to cannily reinvent himself through a series of pop-leaning guest features in the ensuing years – from British group Clean Bandit’s chart-topping single Rockabye in 2016, to Sia’s Cheap Thrills that same year, and the Dua Lipa feature No Lie in 2017.

In Jamaica, new dancehall acts are crossing over into the mainstream, especially female artists. “I’m really proud to see the ladies work the business, as there used to only be a handful, and now there are so many coming up and finding success,” he enthuses. “One of the most exciting stories in Jamaican music right now is Shenseea. She’s a package for me – she sings well and she can spit hardcore when she’s ready.” He also namechecks singers Koffee, Jada Kingdom and Naomi Cowan as ones to watch. “This music is all about reflecting what is happening in your community and the new generation are making it their own,” he says.

Indeed, with his own children and the spectre of the school run looming when he returns from this press tour, Paul is spending increasing amounts of time outside the studio thinking about the fate of future generations. Since contributing to the 2015 fundraising single Love Song to Earth, he has noticed the effects of global heating getting closer to home, including Hellshire beach in Kingston slowly disappearing. “When people talk about reaching a point of not being able to go back, I think we’re pretty much past it, so we need to act now to do whatever we can,” he says. He has just finished fitting out his home with solar power and is planning to change to electric cars.

Equally, after Prince William and Kate Middleton’s gaffe-prone Caribbean Commonwealth tour, where they faced calls to make Jamaica a republic and to pay reparations for slavery, Paul has also been thinking about the political future of his country. “It’s weird for me because my grandmother is from Coventry and she feels a strong connection to the royal family – she woke up at 4am to watch Prince Charles and Diana get married and she still has the cups with their faces on,” he says with a laugh. “But then my friends who live in the ghetto feel like, what are they doing for us? So I understand both sides. Emotionally, there is a nostalgia there but as an adult, I feel like: what is it for?”

At 98, his grandmother will be waiting for his visit when Paul returns, perhaps with a plate of the bubble and squeak she used to make for him as a child. “We’re all mixed up as a family – we have the Henriques on my dad’s side and then my grandmother who married a Chinese Jamaican man and came to Jamaica in the 50s,” he says. “I see the positives in the whole mix – we really have to celebrate each other while we have the time.” Perhaps this is Paul’s finally realised act of consciousness. It’s in the party, in the mix, that we come together; it’s to his music that we can put aside our differences and dance.

Source: The Guardian